Backpressure for dummies

A toy example showing how lacking backpressure may lead to failures and how to add it.

Several ideas worth remembering from Sandi Metz’s book 99 bottles of OOP

I quite enjoyed reading 99 bottles of OOP. It strikes a great balance in giving both general principles, that should help you develop a programming aesthetic, and also pragmatic techniques, that could be used directly until you haven’t developed the aesthetic taste you need to guide you.

Below I either summarised some of the points touched by the book, either quoted directly passages that I thought were worth remembering (and reading again from time to time). Also, I grouped them by theme, so that it’s easier to navigate them.

Nice things about the book:

If you were to summarize in a paragraph what this book would like you to achieve:

Well-designed object-oriented applications consist of loosely-coupled objects that rely on polymorphism to vary behavior. Injecting dependencies loosens coupling. Polymorphism isolates variant behavior into sets of interchangeable objects that look the same from the outside but behave differently on the inside.

Questions to ask yourself when you wrote some code and you wonder about its…

…. clarity:

…. maintainability:

…. reducing differences and isolating abstractions:

…. code smells:

Something which I strongly believe in but that I am sure I didn’t really always respect

Voluntarily altering working code costs money, and doing so declares that you believe that rearranging this code right now is more important than anything else on the backlog

Is the opportunity cost of some refactoring worth more than anything else in the backlog?

While refactoring, you should find the things that are most alike, find the smallest difference between them, and then decide what this difference means. Once the difference is isolated the two original things are now the same abstraction, and the difference is a different, smaller abstraction. This should be named and encapsulated in a method or object.

Making existing code open to a new requirement often requires identifying and naming abstractions. The Flocking Rules concentrate on turning difference into sameness, and thus are useful tools for unearthing abstractions.

An approach that I can re-use, It becomes easier to see how things are different if you make them more alike, so, rather than trying to understand everything at once, try to make the things that you are comparing more alike by doing small changes, and then ask yourself what the difference left is representing and whether it makes sense to create an abstraction for it.

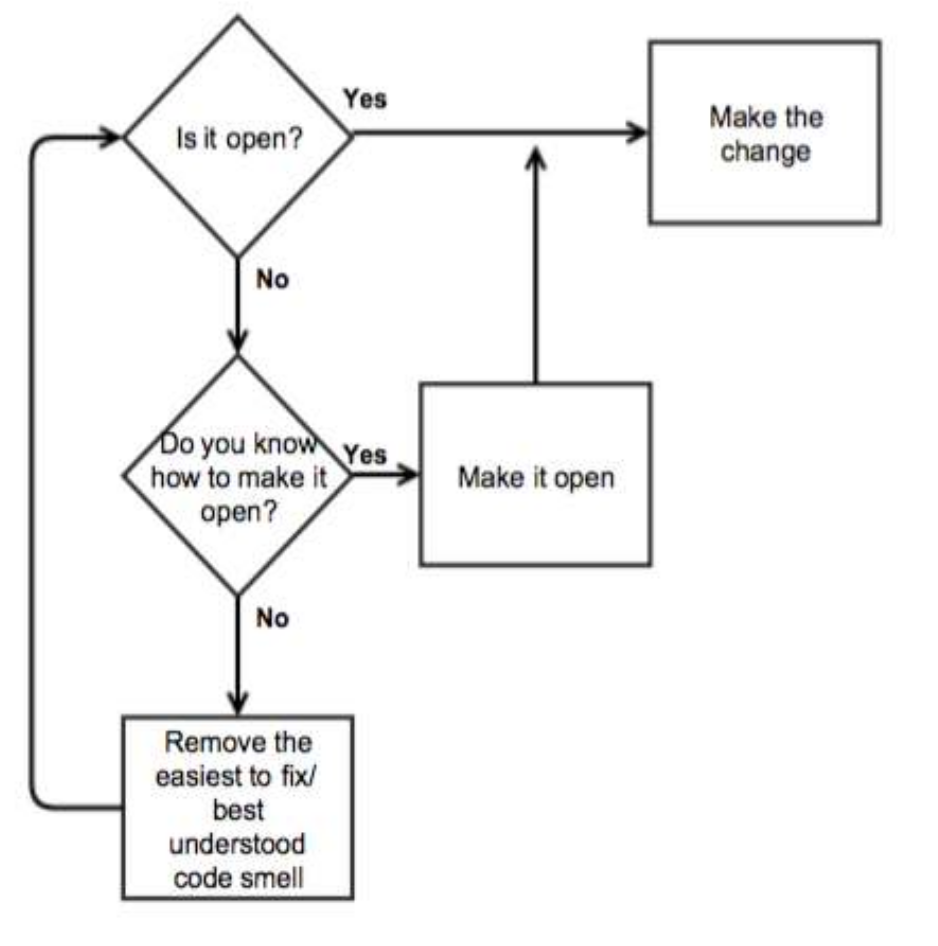

When a requirement comes in I should ask myself, is my code open to be extended with the new requirement? (open-closed principle) if not, do I know how to make it open? if not, can Identify some code smell that’s worth fixing?

Refactor the existing code to be open to the new requirements first, and then focus on adding the new code. The first step can be facilitated by identifying and removing code smells, which ideally would make appear a new path. This step is completed once you can easily extend your implementation. Alternatively, it may be easier to open the code by identifying abstractions. The Flocking rule can help, by forcing you o identifying sameness and differences and making you isolate the differences, and creating separate abstractions.

If the Open-Closed flowchart questions don’t help, simply adding the new requirements with a direct and potentially dirty change may be the better choice. Adding such a change may expose what kind of refactoring is needed. This direct change will possibly introduce a new code smell, which may now appear as a known problem having a known solution.

Refactoring should be requirements-driven. Rather than speculating on how the code will need to change it’s better to wait for new requirements that will state this explicitly.

The requirement reveals exactly how you should have initially arranged the code.

It just so happens that solving easy problems sometimes transmutes hard problems into easy ones. It is common to find that hard problems are hard only because the easy ones have not yet been solved

Proper refactoring only allows to explore a domain safely, it doesn’t carry any guarantee about the fact that the result will better represent the problem. A good definition of abstractions allows for implementing separation of responsibilities.

Refactoring allows extracting abstractions from the current implementation and by doing so also separating responsibilities. Vertical refactoring , methods are moved up or down the call stack or objects end up being wrapped in others, we would keep the same or reduce the number of calls happening on the main script. Horizontal refactoring, in this case, we would end up moving methods to the same level and have most of them being called explicitly on the main script. This approach leads to more flexibility and complexity. (good URL). Always keep separate horizontal and vertical refactoring.

Something I really liked is how easy she makes appear big changes. Mainly thanks to her process-oriented way of picking as the next step the most obvious bad smell and addressing it. Rather than visualizing where she wants to bring the codebase and doing all the changes necessary to move it there she simply focuses on fixing individual bad smells and slowly but consistently the code quality increase but also new opportunities for improving it arise.

Each refactoring followed a recipe, which led to a stable landing point, which in turn enabled the next refactoring. This most recent transition arguably achieves the greatest conceptual leap by way of the least complicated recipe. The ease with which it occurred is a tribute to the efficacy of earlier refactorings.

Wishful thinking : write the interfaces you wished abstractions had and make them happen.

You want to write intention-revealing code. Eg substituting if-else with case-when

When writing a new feature opt for an easy-to-understand, intention-revealing but possibly hard-to-change implementation first ( Shameless Green ).

DRY is possibly one of the easiest to understand and apply principles of software development. For these reasons, it’s also easy to abuse it.

It is cheaper to manage temporary duplication than to recover from incorrect abstractions.

When unsure about adding some extra abstraction or not ask yourself what is the future cost of doing nothing now? and how soon will I get more information? It’s better to tolerate duplication than to anticipate the wrong abstraction.

Duplication is useful when it supplies independent, specific examples of a general concept that you don’t yet understand. For example, in the prior section, the case statement within verse evolved to contain four different templates. Those templates are concrete examples of a more generic verse. Each supplies unique information, but together they point you towards the underlying abstraction.

Abstractions should be unambiguous. One way of evaluating the degree of ambiguity is by assessing how much duplication is removed. If by introducing some duplication you supply no new info to the problem space you should try to get rid of that duplication.

One of the advantages of shameless green is that it forces you to reach a fully implemented version of the feature before trying to define any abstraction. Now the full problem space lays in front of your eyes, no part of it is hidden behind potentially premature abstractions.

you should name methods after the concept they represent rather than how they currently behave

The general rule is that the name of a thing should be one level of abstraction higher than the thing itself. The strings “bottle/bottles/six-pack” are instances of some category, and the task is to name that category and to do so using language of the domain.

The name you choose will be the name you use in conversations with your customers. Naming things after domain concepts improves communication between you and the folks who pay the bills. Only good can come of this.

Good naming implies that you spent time thinking about what concepts you may want to represent and therefore what abstraction is appropriate. Names shouldn’t be too general nor too specific.

Good naming is also important for polymorphism. Tight coupling between the method and the class name (or its context in general) will make it necessary to change the method name and make it more general before being able to use it in a polymorphic way.

Naming things correctly is quite important, and it’s worth spending time on that. However, it takes a while to understand the domain in a decent way, and tests definitely help with that. So, it may be worth only invest time on naming once you have written some tests and you have more clarity about the domain.

Class names should refer to concepts in the application domain, so they should not contain references to patterns names (ie OOP design patterns).

The reason you’re writing tests is to save money, and every potential test must be evaluated against that criteria.

Benefits of testing:

Integration tests are intended to prove that groups of objects collaborate correctly; they show that an entire chain of behavior works …Integration tests are great at proving the correctness of the collaboration between groups of objects. They demonstrate the overall operation of all or a subset of your application. They are usually slow

unit tests … help you write down, communicate the expected behavior of, prevent regression in, and debug smaller units of code When something goes wrong, it’s the unit tests that provide an error message near the offending line of code. Since they narrow the set of potential code culprits behind any problem, they make debugging easier. They should be fast

Each class should have its own unit tests unless its implementation is so simple that adding tests would increase the cost rather than creating benefits. A good test coverage implies that almost 100% of the code gets exercised by the tests, rather than 100% of the methods have its own test/s.

When writing production code one of your top priorities is writing easy-to-change and manage code, patterns, and rules help to achieve this objective. On the other hand, with the testing code, one of the top priorities is writing intention-revealing code. So, the same patterns and rules that you stick to for the production code may not be relevant in this other context.

The discussion about whether or not it makes sense to test BottleNumber objects directly or to test them through BottleVerse is quite interesting. It is so dependent on that example that it is probably better reading it directly from the text, than summarised. In a nutshell, the tight coupling between BottleVerse and BotteNumber combined with the simplicity of the latter make it legit to test both by testing BottleVerse only. While the loose coupling between Bottles and BottleVerse makes it more sensible to test both.

Tests allow to explicitly state examples of the inputs and outputs, the main use case for the code, as well as what edge cases are handled and how. Tests as documentation of the behaviour are particularly important when this is complicated or implicit (eg the BottleNumber factory in the book)

Unit tests ought to tell an illuminating story. They should demonstrate and confirm the class’s direct responsibilities, and do nothing else. You should strive to write the fastest tests possible, in the fewest number necessary, using the most intention-revealing expectations, and the least amount of code.

They help identify design problems that will make code harder to re-use. Examples of this are:

It should be easy to create simple, intention-revealing tests. When it’s not, the chief problem is often too much coupling. In such cases, the solution is not to write complicated tests that overcome tight coupling, but rather to loosen the coupling so that you can write simple tests.

Testing is the first form of re-use. the amount of test setup needed will tell you how tightly coupled the abstraction being tested is to the actual context and how easy it would be to re-use it in different ones.

Writing tests forces you to clarify your intentions exactly and explicitly. This is particularly useful when thinking about the abstractions you want to define and the relative responsibilities.

Writing test that don’t need to change with change in code is probably one of the trickiest parts of writing good tests

A great deal of this pain originates with tests that are tied too closely to code. When this is true, every improvement to the code breaks the tests, forcing them to change in turn. Therefore, the first step in learning the art of testing is to understand how to write tests that confirm what your code does without any knowledge of how your code does it.

Tests are not the place for abstractions, they are the place for concretions. Abstractions belong in code. If you insist on reducing duplication by adding logic to your tests, this logic by necessity must mirror the logic in your code. This binds the tests to implementation details and makes them vulnerable to breaking every time you change the code.

The tests written while doing TDD are only meant to make it easier to write the implementation needed. They are not necessarily good automated tests, actually, they are likely to slow down changes

The SOLID principles are often mentioned in the book. I am not going to describe them but only mention some interesting use of them.

The more decoupled your code the easier it will be to handle unexpected requirements. Applying OOP principles should help loosen coupling, but also increase the amount of code and add levels of indirection. Still, the gain in decoupling will generate enough savings to justify them.

The book provides an interesting by-product of the Liskov Substitution Principlei . The principle implies that the consumer of an API should expect consistent outputs from the APIs it consumes. So, a method/function should always return the same type.

A practical example of the Open-Closed principle violation. If a method is aware of how its behavior should change given a specific argument value it’s a code smell. In this case, a change in behavior will also require the method to change. This pattern suggests that objects are missing. Good use of conditionals in OOP is the one deciding what objects should be used given certain conditions, rather than supplying behavior.

The implementation of the abstractions logic should not be coupled with the logic used in the other classes or the overall logic of what we want to achieve (general context).

Omitting quantity and container methods in favor of jamming “1 six-pack” directly into to_s corrupts BottleNumber6 with knowledge of the inner workings of the Bottles verse template. This expectation couples BottleNumber6 to the context in which it was discovered, and this coupling interferes with your ability to reuse the bottle number classes when new contexts appear.

When discussing how to make the Bottle factory open it is proposed to dynamically define the class name by combining the base class name with the number passed as an argument. I didn’t particularly like this option, but I really liked how she argues that as with most design choices whether it could be appropriate or not depends on the context. Any design choice has trade-offs, including the one of dynamically defining names. The negatives of this option could be offset by the benefit of not having to constantly change the factory in a context in which you need to add options very frequently. The overall reasoning behind applying a specific design is minimizing cost, so whether or not a specific design will do so is very context-specific.

A Blank Line in a function is a code smell, it’s likely to be the case that there is a violation of the Single Responsibility Principle .

Dependency inversion is fundamentally based on isolating the behavior you want to vary. Dependency injection permits to expand and support new behaviors without having to change existing code.

The key to understanding the principle is to recognize that your code should depend on abstractions. If you stumble upon code that’s in the state of depending on concretions, DIP says that you should invert those dependencies and depend upon abstractions instead.

Don’t be trapped by what’s currently true, but instead, loosen coupling by designing a conversation that embodies what the message sender wants.

To make Demeter's Law definition fit a single line we may say that: “an object may talk to its neighbors but not to its neighbor’s neighbors”. Not violating the law of Demeter with dependency injection implies sending messages only to the object being inserted and not to all his friends.

Breaking Demeter law and doing several nested calls leads to tight coupling across many objects which lead to two problems:

The Law of Demeter is the reason why you should pass instances as dependencies, rather than classes or factories.

Sometimes Demeter Law violations may be fixed by simply writing a forwarding method. In more complex cases it may be necessary to know the method argument value in order to instantiate an object needed within the method implementation. In these cases, we can add to the soon-to-be instantiated object class a method taking care of the instantiation itself (ie a factory) and the original method calling as well.

I really liked the two statements below:

Applications that use dependency injection evolve, naturally and of necessity, into systems where object creation begins to separate from object use. Object creation gets pushed more towards the edges, towards the outside, and the objects themselves interact more towards the middle, or the inside.

resist giving instance methods knowledge of concrete class names

They both refer to the same idea that the internals of each object should be unaware of its context (other classes names) and work happily in this state of ignorance. However, the first one seems mainly an idealistic view of the world, of relatively little pragmatic use. The second on the other hand is uniquely pragmatic, to the point of sounding like a dogma. I am not sure I would know how to use any of the two if considered on its own, however, when combined they appear quite complementary. This is just an example of Sandi’s ability to present both the ideal state you should strive for and very pragmatic techniques to reach it. This is probably what I valued the most in the book.

Time taken to write post: 10 hours

A toy example showing how lacking backpressure may lead to failures and how to add it.

A simple piece on how to patch objects and use pytest fixtures in tests at the same time

Using various tools to make python environments working automagically also with emacs

On the benefits of documenting your work and how it can impact your share of the pie

Looking back at 2021 to look forward at 2022

Several ideas worth remembering from Sandi Metz’s book 99 bottles of OOP

Can we do better than a straightforward pickle.dump?

Why interviewing time to time is useful and what I learned so far by doing so

Interesting readings of the month

Interesting readings of the month

Use case of the Strategy pattern in a data science application

Interesting readings of the month

Considerations on how practicing writing can help improving how we communicate and how we think

an overview of what eigenvectors and eigenvalues are and why they make PCA work

A possible pattern for replicating programmatically AJAX POST requests when scraping webpages using Scrapy