Backpressure for dummies

A toy example showing how lacking backpressure may lead to failures and how to add it.

A toy example showing how lacking backpressure may lead to failures and how to add it.

TL;DR A backpressure mechanism enables a component of a workflow (service, consumer, step in pipeline, etc) to push back against too much input so that it can avoid overloading under the pressure. This blog post uses a toy example to show the consequences of lacking backpressure in a service doing async calls and also a possible way to add it.

It took me a bit of time to understand what backpressure is about. I finally got a decent understanding after reading “I’m not feeling the async pressure” from Armin Ronacher. This post shows a toy example, based on Ronacher’s article, that is meant to show what happens when backpressure is lacking in an async service and how to add it.

The toy example, which you can find on github, defines a FastAPI app exposing 3 endpoints. Each endpoint is implemented slightly differently but fundamentally they all perform the same set of operations under the hood, one IO-bounded operation wrapped in two CPU-bounded ones. Also, each CPU-bounded operation artificially increases the memory footprint of the single request process, so that it’s easier to overload and make fail the service with a small number of requests. The IO-bounded operation is simply implemented calling time.sleep(2) and blocking the execution for two seconds. The time.sleep let us simulate the process of waiting for the IO operation to complete.

The service performance mainly focuses on two things, how long does it take to satisfy all the requests, and whether the service will be able to handle them or it will be overloaded and flip over. The service may flip over if it ran out of memory (this is the failure mode we are going to use in the blog post). We can run the service from within a Docker container with a fairly low --memory value, so that we can keep the memory available arbitrarily low and make it easier to test its reliability.

1

2

docker build . -t backpressure

docker run --rm -p 8080:80 --memory=200m backpressure

The performance of the 3 endpoints is being tested by simply sending them a few requests (12) concurrently. Below is the snippet showing how the requests are being sent:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

async def get(session: aiohttp.ClientSession, value: int, url: str, retries: int = 10):

"""Sending a request to `url` from within an async session.

The method supports retries as long as the response status code

received is a 429. This is because backpressure will be implemented

by sending a response with that status code straightaway whenever

the service is under high load

"""

while retries>0:

url_value = f"{url}/{value}"

logging.info(f"requesting {url_value}")

resp = await session.request("GET", url=url_value)

if resp.status == 429:

retries -= 1

logging.info(f"Got a 429 for {url_value} - retrying")

await asyncio.sleep(0.3)

continue

else:

logging.info(f"completed request for {value}")

break

data = await resp.json()

return data

async def run_many_requests_concurrently(url:str, number: int):

async with aiohttp.ClientSession() as session:

tasks = [get(session=session, url=url,value=i) for i in range(number)]

vals = await asyncio.gather(*tasks, return_exceptions=True)

return vals

async def query_endpoint(endpoint_name: str, number: int):

logging.info(f"Start querying the {endpoint_name}")

URL = f"http://127.0.0.1:8080/{endpoint_name}"

start = time.time()

await run_many_requests_concurrently(url=URL, number=number)

end = time.time()

logging.info(f"time spent: {end-start}\n\n\n")

if __name__ == "__main__":

number = 12

asyncio.run(query_endpoint(endpoint_name="sync_endpoint", number=number))

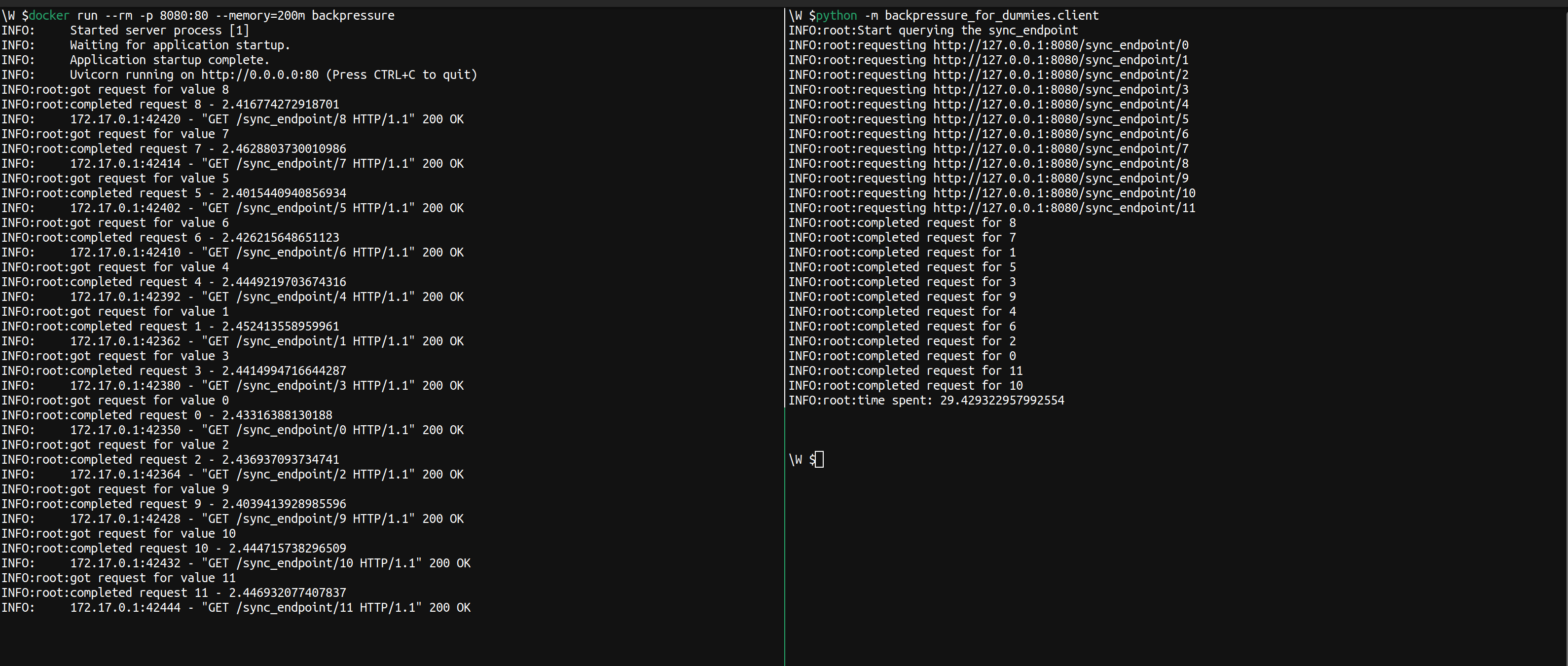

As mentioned each endpoint is meant to represent a slightly different implementation. Let’s start with the simplest one, executing all work synchronously.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

@app.get("/sync_endpoint/{value}")

async def sync_endpoint(value: int):

logging.info(f"got request for value {value}")

start = time.time()

_ = _compute(value) # preprocessing state

_io(value)

_ = _compute(value) # postprocessing state

logging.info(f"completed request {value} - {time.time() - start}")

return {"message": value ** 2}

In this case, the blocking IO call _io prevents the process from doing any work while it is idle and waits for _io to return. This endpoint takes roughly 30 seconds (on my machine) to complete the 12 requests.

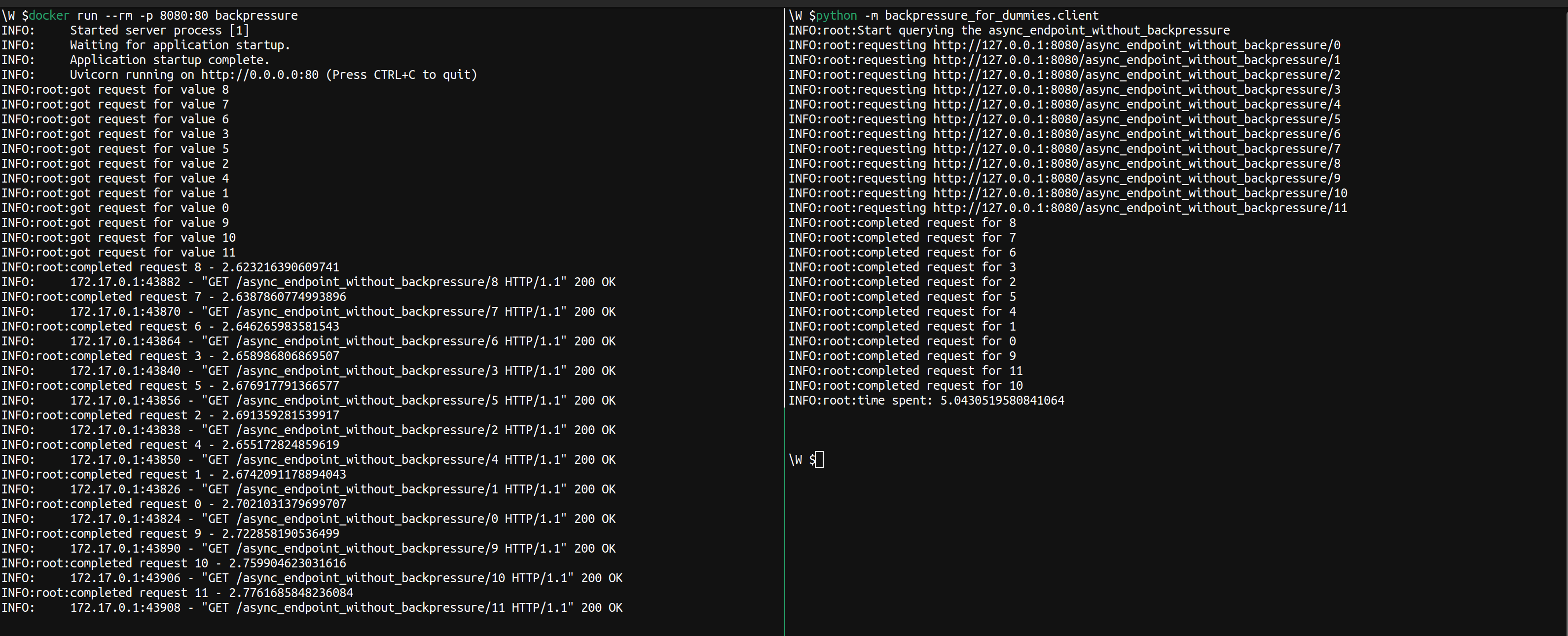

Given that the workflow includes a blocking IO operation we can improve performance by executing the _io step asynchronously.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

@app.get("/async_endpoint_without_backpressure/{value}")

async def async_endpoint_without_backpressure(value: int):

logging.info(f"got request for value {value}")

start = time.time()

_ = _compute(value) # preprocessing state

await _async_io(value)

_ = _compute(value) # postprocessing state

logging.info(f"completed request {value} - {time.time() - start}")

return {"message": value ** 2}

This effectively frees the thread that in the sync_endpoint workflow was waiting for _io and lets it do other work in the meantime. In the _async_io function we also replace the time.sleep call with the non-blocking asyncio.sleep one. In an actual IO scenario this would be similar to do the IO call using an asynchronous python library, rather than a synchronous one. This almost makes it so that all the _io calls are running concurrently and the asyncio.sleep(2) partially overlaps.

That was fast, very fast. With the synchronous endpoint, we had to wait for each request to be completed before we could move to the next one. So, for each request, we would just wait 2 seconds doing no work. Now by introducing the async await for the IO we can switch control to handle another request, and then go back to the original one once the async call has been completed. This effectively makes it so that the 2 seconds for the requests are almost “waited” all at the same time, rather than sequentially one after the other as before.

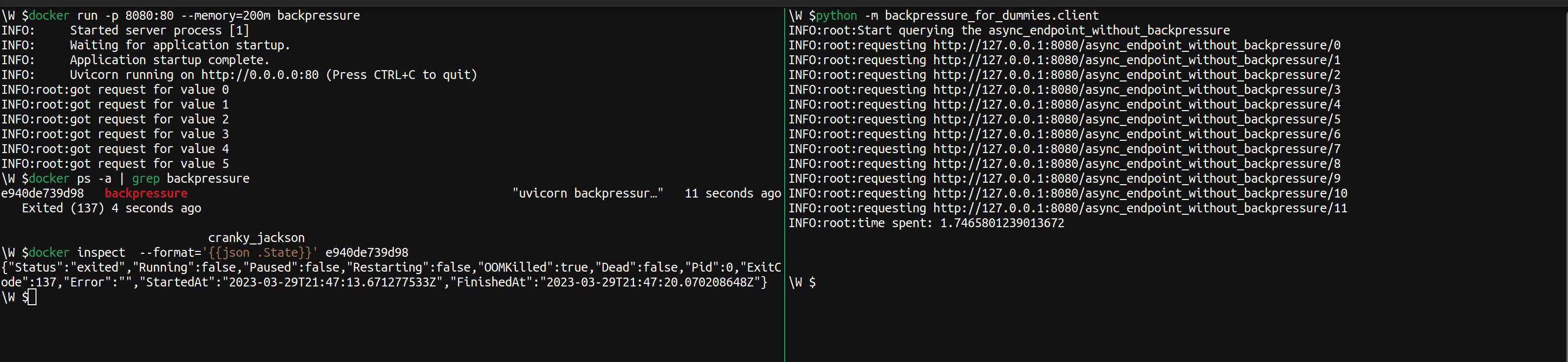

However, what happens if we get enough requests that the memory footprint of the output resulting from the first call to _compute is too much to handle? as mentioned we can easily simulate a server not having enough memory available by setting an upper bound to the memory available to the container where the service runs.

We don’t have enough memory to handle so many requests all happening at the same time, and the container, as well as the service, get OOM killed. This is a simplified example designed to fail fairly easily. Still I think the failure mode should remain for most services accepting an unbounded number of requests handled asynchronously. This failure mode exists because the service lacks a backpressure mechanism. The service has no way of pushing back against clients’ pressure and somehow preserving an acceptable level of workload. Again I recommend reading Ronacher’s post on the topic.

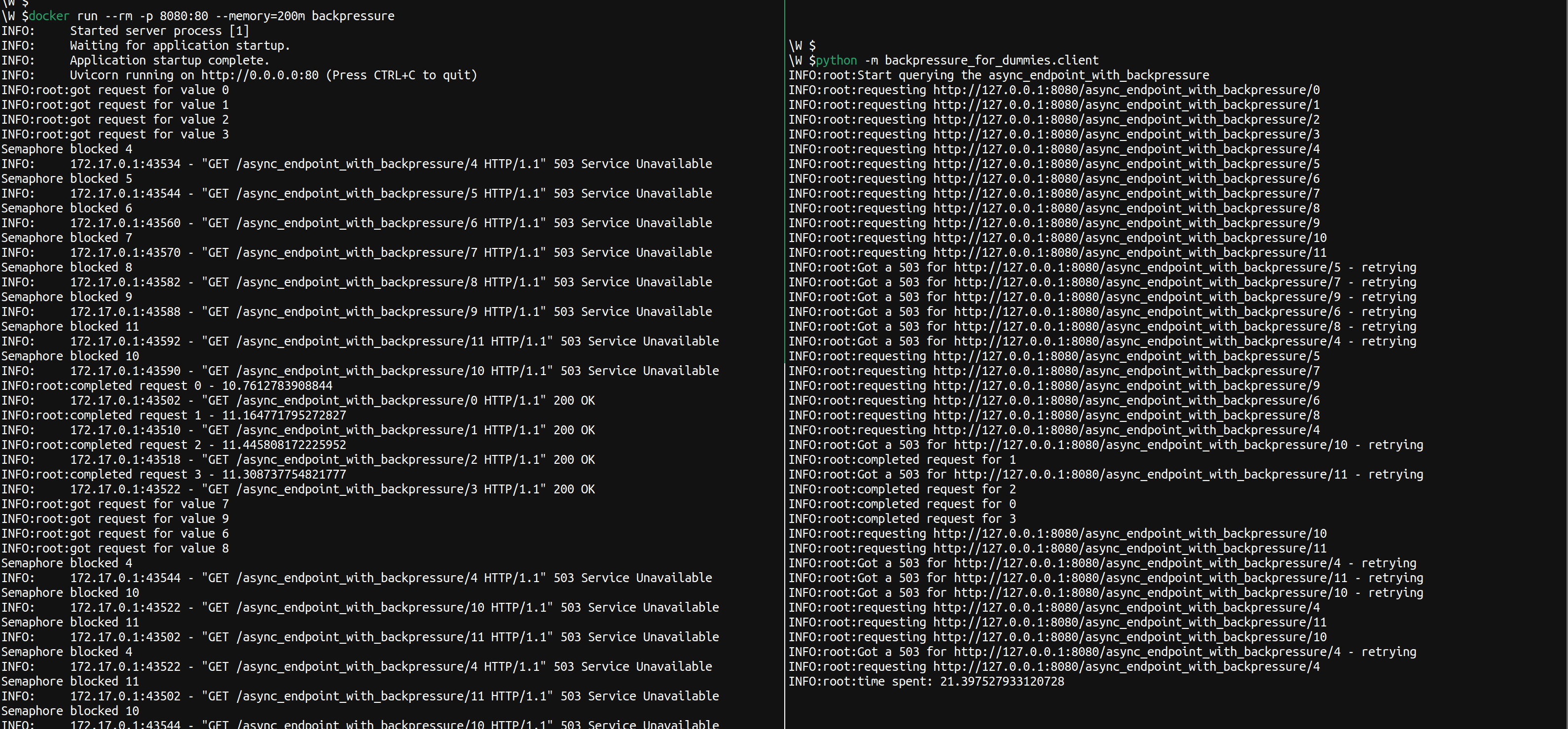

Let’s implement backpressure following one of the suggestions in Ronacher’s article by using a semaphore.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

@app.get("/async_endpoint_with_backpressure/{value}")

async def async_endpoint_with_backpressure(value: int):

global sem

if sem.locked():

print(f"Semaphore blocked {value}")

raise HTTPException(

status_code=status.HTTP_429_TOO_MANY_REQUESTS,

detail="server overloaded"

)

await sem.acquire()

try:

start = time.time()

logging.info(f"got request for value {value}")

_ = _compute(value) # preprocessing state

await _async_io(value)

_ = _compute(value) # postprocessing state

logging.info(f"completed request {value} - {time.time() - start}")

return {"message": value ** 2}

finally:

sem.release()

So, now we are going to use a semaphore to check whether the service has enough capacity to handle more requests. If it doesn’t, because it’s already handling as many as the semaphore allows for, then it will return a response with a status code 429. This is still going to let us process requests concurrently by switching over them when we call async await as we were doing with the async endpoint, but only with a smaller number of requests. Any other request beyond this number will be rejected straightaway by the service, letting then the client decide how to deal with it.

This endpoint is slower than the async one without backpressure. However, it is still faster than the synchronous one. Also, thanks to the backpressure mechanism we removed the failure mode shown in the previous section. We can still improve the performance by simply increasing the semaphore counter, we just need to make sure we have enough memory to handle more requests or reduce their memory footprint.

The lack of backpressure can make a component run out of resources and fail. Phelps’ article and Ronacher’s one give respectively a good overview of what backpressure is and also how not considering it when using async frameworks may expose a component to failures.

Both articles should be enough to give an intuitive understanding of what backpressure is and an idea of when it may be needed. This article further solidifies the understanding of these two concepts by providing a toy example in which we initially make a system more performant by introducing async calls, but we also expose it to the kind of failures backpressure should prevent. Backpressure is then introduced through a semaphore making the relative endpoint more performant, compared with the initial one, and also introducing a check to prevent the service from being overloaded.

Time taken to write post: 6 hours

Thanks for reviewing to Declan Crew

A toy example showing how lacking backpressure may lead to failures and how to add it.

A simple piece on how to patch objects and use pytest fixtures in tests at the same time

Using various tools to make python environments working automagically also with emacs

On the benefits of documenting your work and how it can impact your share of the pie

Looking back at 2021 to look forward at 2022

Several ideas worth remembering from Sandi Metz’s book 99 bottles of OOP

Can we do better than a straightforward pickle.dump?

Why interviewing time to time is useful and what I learned so far by doing so

Interesting readings of the month

Interesting readings of the month

Use case of the Strategy pattern in a data science application

Interesting readings of the month

Considerations on how practicing writing can help improving how we communicate and how we think

an overview of what eigenvectors and eigenvalues are and why they make PCA work

A possible pattern for replicating programmatically AJAX POST requests when scraping webpages using Scrapy